By Jackie Stapleton

I was reading an article recently, and while I can’t remember where it was published, one small detail stuck with me. The author mentioned how many times the word “change” appears in the draft version of the forthcoming revision of ISO 9001 compared to the 2015 version. That single comment was enough to make me stop and dig a little deeper.

So, I decided to check it for myself.

When you look closely at ISO 9001:2015, change is already mentioned, and it appears more often than people sometimes realize. It shows up across leadership, planning, process evaluation, corrective action, improvement, and management review. In total, the word (including “change,” “changes,” and “changed”), appears 34 times.

But what’s interesting isn’t just the count. It’s the way change is treated.

In the 2015 revision, change is generally framed as something that interrupts an otherwise steady system. It’s something to be considered, controlled, evaluated, and documented so the integrity of the quality management system is maintained. The underlying logic is that the organization has a relatively stable baseline, and when change occurs, the system’s job is to absorb it without losing control.

The ISO/DIS 9001 seems to work from a different assumption entirely.

It assumes that organizations operate in environments that are constantly moving, where context shifts over time, risks evolve rather than stay fixed, customer expectations change, supply chains are disrupted or reshaped, technology advances at a pace most systems struggle to keep up with, and people move in and out of roles, taking knowledge and experience with them.

In that kind of reality, change is no longer an occasional disruption to be managed, but the normal operating condition the system has to function within.

That’s why the word no longer sits in one or two clauses. It’s woven through context, leadership, risk and opportunity, process effectiveness, performance evaluation, and improvement. The system is no longer being designed to withstand change when it happens. It’s being designed to stay effective while change is happening.

So, this isn’t about suddenly realizing that change is constant. Anyone who has worked with ISO 9001:2015 in the real world already knows that. Organizations have been dealing with shifting context, evolving risks, changing customer expectations, and operational disruption for years.

What’s different in the draft is that the standard finally reflects that reality more openly.

Rather than treating change as something that occasionally needs to be planned and controlled so the system can return to a steady state, the draft assumes movement as the baseline. It recognizes that quality management systems are expected to remain effective while things are changing, not just once the change has settled.

That’s the significance of seeing the word “change” embedded throughout the draft. It’s not a revelation for practitioners. It’s an alignment.

ISO 9001 hasn’t discovered change. It’s acknowledged it.

This idea isn’t unique to ISO, either. Mainstream business thinking has been saying the same thing for years. In a recent Harvard Business Review article, “Why Keeping Up With Change Feels Harder Than Ever,” the focus is on how organizations are now operating in environments where disruption, uncertainty, and competing priorities are constant, making the ability to adapt more of a core leadership capability rather than a periodic exercise.

Forbes makes a similar point in “Organizations Need To Shift From Change Management to Change Fitness,” arguing that organizations need to move beyond treating change as something to manage occasionally and instead build the capability to remain effective while things are shifting, rather than waiting for stability to return.

How ISO 9001’s treatment of change is shifting

If ISO/DIS 9001 is working from a different assumption about how organizations operate, then it follows that the way we think about change inside a quality management system also needs to shift.

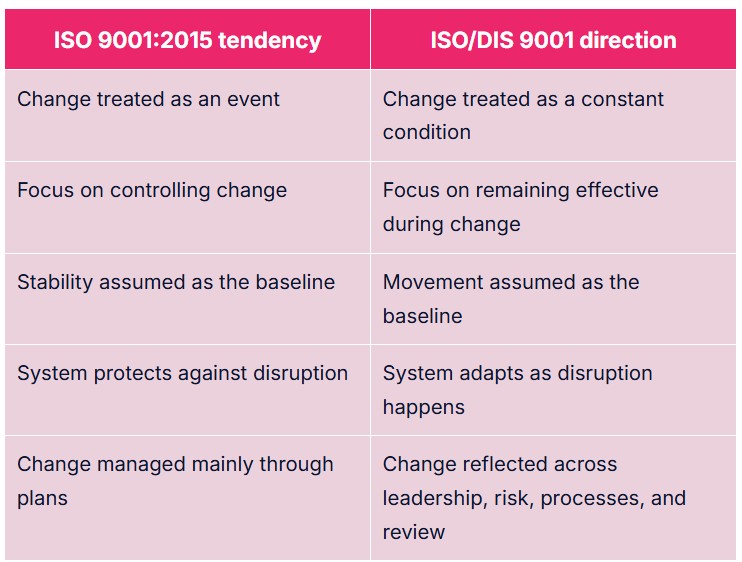

It’s not about adding new procedures or rewriting documents, but about understanding how the standard’s expectations have moved. One way to make that shift clearer is to look at how change is treated in the 2015 revision compared to the draft:

Each of these shifts shows up in practice in slightly different ways:

- Change treated as an event → Change treated as a constant condition. Traditionally, change triggered a formal response such as a project, review, or approval, whereas the draft assumes ongoing movement and expects the system to function without waiting for things to settle.

- Focus on controlling change → Focus on remaining effective during change. The emphasis moves from managing approvals and version control to asking whether processes continue to deliver intended results while priorities, inputs, or constraints are shifting.

- Stability assumed as the baseline → Movement assumed as the baseline. The 2015 revision implicitly worked from a steady-state view of the organization, while the draft starts from the assumption that context, risks, and expectations are always in motion.

- System protects against disruption → System adapts as disruption happens. Instead of designing systems to absorb shocks and return to normal, the draft expects systems to adjust and keep working as conditions change.

- Change managed mainly through plans → Change reflected across leadership, risk, processes, and review. Rather than containing change in planning activities, the draft spreads responsibility across leadership behavior, risk thinking, operational decisions, and ongoing review.

What ISO 9001:2026 effectively does is build flexibility into the quality management system by design, rather than relying on workarounds when things change. Most experienced practitioners have been doing this intuitively for years. The draft simply makes that flexibility visible and legitimate within the standard.

Your next steps

- Look at where your system assumes stability. Take a step back and notice where your quality management system is built around things staying the same, whether that’s fixed processes, static risks, or reviews that only happen on a calendar rather than in response to what’s actually changing.

- Ask whether effectiveness holds when things move. Instead of asking, “Do we control change?” start asking, “Does this process still work when inputs, priorities, people, or conditions alter?” That’s the test the draft is applying across the standard.

- Start building flexibility by design, not by workaround. Pay attention to where your system relies on informal fixes or experience in people’s heads to cope with change and consider how those adaptations could be reflected more deliberately in leadership behaviors, risk thinking, and system reviews.