By Nuno F. Soares, Ph.D.

Who hasn’t felt nervous before an audit? There is a great deal of pressure today on food safety professionals to achieve successful audits, especially when we have a big client requiring it or a certification body doing it. Most of us neglect the fact that audits should be perceived as one (more) powerful tool in the continuous improvement of our food safety system.

Audits

What is an audit? Probably one of the most commonly used audit definitions is the one provided by ISO 19011 “Guidelines for auditing management systems.” In its last update (2018) the ISO document defines an audit as a systematic, independent, and documented process for obtaining objective evidence and evaluating it objectively to determine the extent to which the audit criteria are fulfilled. In this definition ISO decided to reinforce the importance of the evidence being objective because the only change from the 2011 definition was the substitution of audit evidence for objective evidence.

More details can be found in the GFSI definition for audits present in the GFSI Benchmarking Requirements version 7.2: A systematic and functionally independent examination to determine whether activities and related results comply with a conforming scheme, whereby all the elements of this scheme should be covered by reviewing the supplier’s manual and related procedures, together with an evaluation of the production facilities. Clearly, the commonality is that audits should be systematic and independent processes to determine compliance with criteria.

As a systematic process, auditing has two main roles:

- Validating that the food safety systems are planned and built to fulfill the criteria

- Verifying that the activities performed comply with what is planned and are effective

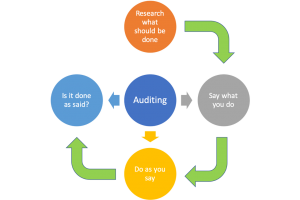

If we think in simple terms, we can divide a food safety system into four steps, as seen in figure 1.

First, we must research what should be done (based on what the organization does, the law, and the criteria or elements of the conforming scheme or system). Second, we must say what we will do; that is, we should define what is planned to fulfill the criteria. But this is not enough. More important even is the third step, which is to do as you say. In their daily work, people in the organization should execute their functions and tasks accordingly with what is established. Fourth and finally, we must have evidence to be sure we can always reply affirmatively to the question: Is a process or procedure executed as planned?

During an audit the auditor should validate what you say you do, then go to the field and verify not only that things are done as said but also look for evidence that they were done as said.

The auditor

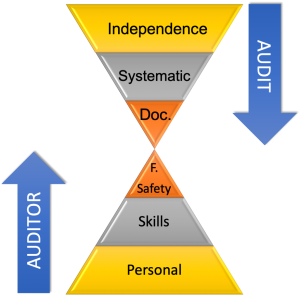

As presented above, during an audit the auditor must be able to validate and verify compliance with criteria or requirements. For that the auditor must have adequate attributes and knowledge. In figure 2, you’ll see the main elements of an auditor and an audit.

If audits are to be used as tools to improve the food safety system, they must be performed independently, be free from bias or conflict of interest, and be systematic and well documented.

Although sometimes it may seem that anyone can be an auditor, that is not the case; at least, it isn’t the case for food safety audits. The first two essential elements in an auditor, personal characteristics and skills, are related with the person and not specific to food safety. Typically, an auditor should have ethical behavior, be an organized and observant person (even curious) and utilize an emphatic and diplomatic approach. The auditor will also benefit from having skills related with how to question or interview people, how to conduct a systematic audit, how to prepare an audit report, and active listening, among others. On the top of the pyramid is of course the knowledge of food safety and the industry. It is paramount that auditors know the law and requirements or criteria that apply to the organization and the product line they are auditing. Education, training, and experience in the field is also a basic requirement and is essential for how much the organization may benefit from the audit.

The future of audits

Assessing and harmonizing an auditor’s knowledge and skills is certainly an important goal for the future. This is important not only to establish a minimal baseline of competencies for auditors but also to establish credibility for the profession and the process. The recent release of a GFSI knowledge exam is a step in that direction, offering a consistent method to assess auditor knowledge across a range of relevant skills for all GFSI-recognized programs. Auditors seeking to audit GFSI-recognized certification programs will find questions about specific technical skills as well as standard auditing skills.

Another aspect that needs to be improved is the perception of the value added by food safety audits. Auditors should do everything in their power (without compromising the independent, systematic, and documented approach) to make the process beneficial to the organization and its food safety system.

Technology is evolving at an outstanding pace but for the moment the adaptation of new tools and technologies to auditing seems delayed. It is not difficult to foresee that technologies like smart glasses can play a role in the future of audits. Mainly people advocate that this tool could reduce travel costs but maybe we should focus more on how this technology could increase the number of audits for the same cost.

About the author

Nuno F. Soares, Ph.D. is an author, consultant, and trainer in food safety. He is a food engineer specialist and senior member of the Portuguese Engineering Professional Association. He has more than 20 years of experience in the food industry as a quality and plant manager. You can reach him at www.nunofsoares.com.