By Tom Taormina

Each article in this series (part one here, part two here, part three here, part four here, part five here, part six here, part seven here, and part eight here) presents new tools for increasing return on investment (ROI), enhancing customer satisfaction, creating process excellence, and driving risk from an ISO 9001:2015-based quality management system (QMS). These articles are intended to help implementers evolve quality management to overall business management. Here, in the final part, we review what we’ve learned and look ahead.

After more than 50 years as a quality control engineer and having worked with more than 700 companies, it is my observation that the vast majority of quality professionals hold their prime directive to be reducing defects to the lowest acceptable level by minimizing process variability. Most of us are working to comply with ISO 9001:2015 or one of the other harmonized standards, so we have templates that direct how we practice our craft.

We employ many tools to plot our progress and solve problems. We use control charts to help us stay within established limits of acceptability. Histograms depict variables over time. Pareto charts tell us the rank order of problems we need to solve. Fishbone diagrams break process issues into their constituent components to help locate critical issues.

We are skilled in root cause analysis and failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA) to diagnose complex issues and identify where corrective actions and process improvements can and should be made. Unfortunately, it is often the case that those who are involved in the processes are the ones attempting to diagnose their own procedures and methods.

Once we have identified processes that are candidates for improvement, we have a toolbox from which to choose the appropriate remedy. We can build a house of quality for a high-level assessment and benchmarking. We can use poka-yoke in efforts to mistake-proof processes.

We can use the 5S techniques to clean up our facilities or do a kaizen event on a specific work area or process. We have quality function deployment and scorecards to help diagnose issues with customers.

At the end of the day, we conduct our jobs much like medical doctors. We diagnose and cure quality diseases and maladies. As with doctors, we are mostly an overhead expense that has developed sets of metrics to demonstrate our worth and how we positively affect process outcomes. We seldom contribute to the overall health of the patient (the company) outside our areas of expertise.

During the 1990s we became more focused on quality management as a profession. One segment focused on training and certification, mostly for compliance to the ISO series of quality management system (QMS) standards. I was on the Quality Management Systems Committee of ASQ for several years and got my CQM (now CMQ/OE) certification in 1996. To date, I have written 10 books on the beneficial use of ISO 9001.

Six Sigma

Another faction of our brethren resurrected a statistical process tool invented by Motorola for mass producing cell phones, and the Six Sigma phenomena was born.

The fathers of Six Sigma saw an opportunity to morph the tools of mass production into defect-reduction techniques that could ostensibly be effective in any industry. Six Sigma ranches and retreats became the rage. Borrowing from martial arts, the progressive “belt” program became very appealing for distinguishing the levels of expertise among the practitioners. Then, Jack Welch implemented Six Sigma at General Electric, and the phenomena took off as the solution to all problems of quality and process variability. It has taken decades to discover that what was effective for a mega-corporation with limitless resources was not as productive a fit for a 50-person manufacturing operation.

According to the holy grail of Six Sigma, the lowest practical level of defects is 3.4 out of every million opportunities. The formula has been used for everything from electronics manufacturing to erroneous business transactions to number of takeoff and landing incidents in commercial aviation.

It may comfort you to know your airline that employs Six Sigma is expecting its best performance to be 12 incidents per million flights. It’s not good enough for me because I have experienced five in-flight, takeoff, and landing emergencies in approximately 1.5 million passenger miles.

In my ongoing (professional) debates with the stalwarts of Six Sigma, my argument always turns to pharma. Is the Six Sigma metric the best the pharmaceutical industry can do? I would be extremely uncomfortable taking my prescription and over-the-counter meds if I thought there was any chance of a wrong or defective pill in a bottle. I worked with a pharma warehouse that had never shipped an incorrect or out-of-date order during the 12 years it was in business.

Forensic business pathology

More than a decade ago, I was approached by an attorney to review a lawsuit involving jet engine parts from a “quality control” perspective. After sifting through piles of evidence and testimony, it was clear that what was needed was a process audit of the defendant, a manufacturer, to determine if it was following its own procedures and the requirements of the AS9100 standard. Unfortunately, expert witnesses seldom get to do a physical surveillance audit, so I had to find the evidence in the paper trail and in discovery (i.e., requested documents from the opponent).

In legal parlance, my audit had to “determine if the defendant company did or did not exercise an appropriate standard of care delivering their product to the stream of commerce.” I have a 96-percent success rate using my methodology, which I have trademarked Forensic Business Pathology.

Of 42 lawsuits, virtually all the defendants were not following their own procedures and/or industry standards. Of those that claimed ISO 9001 certification, none were fully compliant with the standard. In every case where I represented the plaintiff, the root cause of the accident or tragedy was the defendant, consciously or unconsciously, ignoring foreseeable risk.

Foreseeable risk is process variability and operator-error potential that is discoverable if the organization has a viable quality management system, effective training, and leadership that is diligent with respect to its customers.

In cases I have worked, I have seen a defective switch in a space heater cause the death of an entire family. I have testified in a case where a poorly manufactured electrical outlet caused the demise of three children in their sleep. I have seen an outsourced part for a motorcycle cause a sheriff’s deputy to become a paraplegic. I have testified in a case where a “boom box” was not only manufactured incorrectly, but the plastic housing did not meet UL requirements, causing a house to burn down.

About a decade ago, these experiences caused me to have several epiphanies. First, unless you work in a high-risk industry, almost all risk is foreseeable. Second, it is my opinion that the foundational tenets of quality management are fundamentally flawed. Third, working only toward minimizing defects to their lowest practical level is perfecting mediocrity.

Foreseeable risk

My experiences validate the proposition that the creation of defects that lead to exposure and danger is avoidable. Most risk is avoidable because it can be foreseen.

Before I became an expert witness, I was oblivious to the reality that process variability could lead to catastrophic fires, injury, loss of property, and death.

Tools such as FMEA uncover potentially detrimental process inconsistencies in their investigations but are seldom sufficiently in-depth enough to discover foreseeable risk. Preventive action requests (PAR) and the current implementation of risk-based thinking for process improvement are seldom proactive enough to be effective for risk avoidance. Rarely is preventive action a result of an epiphany or a flash of genius. Nor are PARs typically the result of cognitive liability investigations.

Even more uncommon is a formal program of foreseeable risk implemented as an immutable and proactive cultural mandate. The trigger for implementing a mandate of risk avoidance is too often the outcome of a product or service being involved in a massively costly failure or some human tragedy.

Foreseeable risk is a systematic diagnostic method that examines the health of a business using proven tools of process analysis, performance to standards, business metrics, and management system effectiveness.

Used proactively, foreseeable risk is a road map for organizations to achieve peak health and wellness. Used as a forensic tool, it provides documented evidence of the standard of care and foreseeable risk measured against quantifiable standards of performance.

For enlightened business leaders, foreseeable risk is a strategy for achieving peak performance while immunizing the organization from product liability and organizational negligence. By virtually eliminating product defects and service errors, organizations can achieve unparalleled pinnacles of customer service and defect avoidance.

In 2010, I was commissioned by Lawyers and Judges Publishing to write a book about my methods for identifying foreseeable risk. It is mainly a desktop reference to help litigators with their strategies, but it contains guidance for foreseeable risk and risk avoidance for business professionals.

Quality management

Virtually every incarnation of quality management, Six Sigma, lean, or total quality management (TQM) shares the fundamental belief that defects can only be minimized, not eliminated. If a mandate does not exist that a defective product or services will never reach a customer, you will always have defects. Some of these defects will lead to costly warranty or repairs, others to civil litigation.

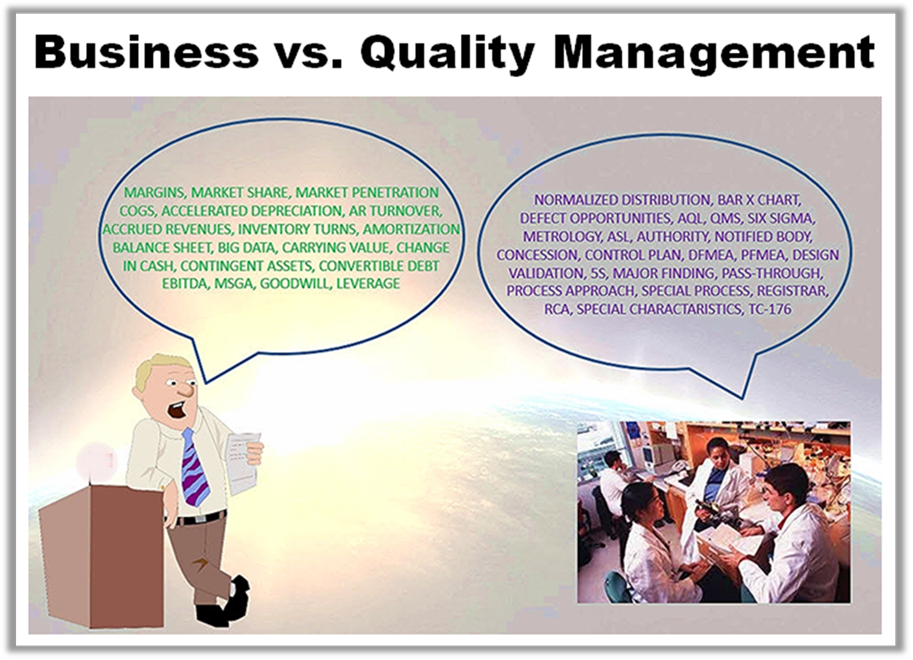

The new paradigm for quality professionals must be that quality management is business management. Key business performance metrics are the only meaningful metrics. We must take the initiative to become the champions of business excellence, not the stewards of process effectiveness.

We can start by learning to speak the language of business.

Risk avoidance

In the documented terms and definitions section of your QMS, add foreseeable risk and risk avoidance. In legal parlance, foreseeable risk is a danger that a reasonable person should anticipate as the result of his actions. Risk avoidance is stopping risk, not managing it. Translated to your organization, this is a new paradigm about process optimization and mistake-proofing.

The definition you adopt should include a new proactivity in process assessment and competence parameters that synthesizes every potential opportunity to introduce errors.

This fishbone diagram is an example of the practical definition of foreseeable risk. In this case, it helped prove negligence. Used proactively, it can help build a risk avoidance culture.

If you operate in an ISO 9001:2015 environment, risk avoidance should be included in each of the clauses of your QMS.

In the context of ISO 9001:2015:

- Defining organizational excellence and risk avoidance in clause 3

- Evolving the requirements of clause 4 from merely defining the context of the organization to working with senior management to create, implement, and make shared vision, mission, and values a cultural imperative

- Redefining clause 5 to include roles and responsibilities for everyone in the organization that are measurable and inextricably tied to the key business success goals and metrics

- Including in clause 6 the tools and culture of risk avoidance

- Evolving clause 7 from support to an outcome-based risk-and-reward culture

- Expanding the scope of clause 8 into a holistic business management system

- Redefining clause 9 from performance evaluation to an enterprisewide culture of individual and team accountability

- Making improvement an organizational imperative in clause 10

Your future as a forensic business pathologist

In the last decade, business leaders have questioned the value of ISO 9001 certification as a necessary business cost. The patina has faded as the standard became a marketing tool. The number of ISO 9001 certifications has fallen 20 percent worldwide.

Similarly, Six Sigma is seeing a decline in popularity for similar reasons, cost vs. benefit. There is a timely article, available here, that makes an in-depth case for how a Motorola statistical tool became a cultural imperative for all organizations, and how it may no longer be. We can fade into history like Jack Welch and quality circles, or we can pioneer the future.

If we, as quality professionals, are to become indispensable assets to our organizations, we must examine our paradigms and become value-adding to the entire enterprise. In my experience, that requires including all aspects of business operations in our experiential knowledge base and becoming champions of the key success goals and indicators of our organizations.

Also, we need to learn how to incorporate risk avoidance in every process in our organizations. The results can lead to zero outgoing defects and creating customers who are referrals instead of warranty nuisances.

By adding the tenets of foreseeable risk into your skill set, you may find that you become a virtual expert in products liability and organizational negligence. That will make you a more valuable asset to your organization. You may find it may also become a lucrative vocation, as I have.

Motivated in part by the positive response to my series on business excellence and risk avoidance published in Quality Digest and Exemplar Global’s The Auditor Online, an effort is underway to create training in and certification for forensic business pathology. Are you a candidate to champion the transition from overhead quality management and risk-based-thinking to being a profit center for your organization, and to becoming the internal expert on foreseeable risk and risk avoidance?

About the author

Tom Taormina, CMC, CMQ/OE, is a subject matter expert in the ISO 9000 series of standards. He has written 10 books on the beneficial use of the standards. He has worked with more than 700 companies and was one of the first quality control engineers at NASA’s Mission Control Center during Projects Gemini and Apollo. He is also an expert witness in products liability and organizational negligence.

This article first appeared on the Quality Digest website and is published here with permission.