by Eugene A. Razzetti

Industrial espionage, hacker and cyberattacks, natural disasters, disgruntled former employees, hazardous materials spills, and terrorist attacks can close an organization indefinitely, not to mention exact a concurrent, incidental toll in personnel or equipment. Organizations have an ethical and economic imperative to assess and harden their security structures. These days, auditors can and should assess the security posture of their organizations through security audits as part of the organization’s overall auditing strategy.

ISO 28000 can help to ensure the security of any organization. It was developed in response to the transportation and logistics industries’ need for a commonly applicable security management system specific to the supply chain. Its main elements are:

- Security management policy

- Security planning (risk assessment, regulatory requirements, objectives, and targets)

- Implementation and operation (responsibilities and competence, communication, documentation, operational control, and emergency preparedness)

- Auditing, corrective and preventive action

- Management review and continual improvement

Organizations already certified to ISO 9001 or ISO 14001 are already well on their way to ISO 28000 certification and to a hardened security posture. The standards mutually support each other, as shown in figure 1. Security-minded auditors and consultants will work with an organization’s existing strategic planning, process management, and documentation to increase security and address more traditional challenges such as efficiency, safety, profitability, and regulatory compliance.

Figure 1: Security audits–Mutually supportive standards

The following ten areas contain segments of a checklist that I use when I perform security audits or consult in ISO 28000.

- Organizing the security management system

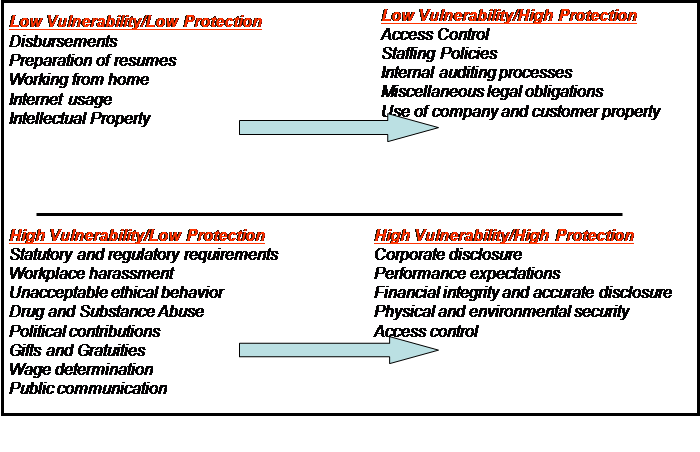

Organizing for security means that the organization must establish, document, maintain, and continually improve an effective security management system for identifying security threats, assessing risks, and controlling/mitigating their consequences. The organization must look at all the functions it performs and assess them in its security audits according to the amount of vulnerability and the amount of protection required, as shown in figure 2. As the arrows suggest, you want to minimize vulnerability and/or maximize protection.

Figure 2: Security audits–Risk matrix

The organization must next define the scope of its security management system, including control of outsourced processes that affect the conformity of product or service. After that’s accomplished, the organization must establish and maintain an organizational structure of roles, responsibilities, and authorities consistent with the achievement of the security management policy, objectives, targets, and programs. These must be defined, documented, and communicated to all responsible individuals.

Top management should provide quantifiable and documented evidence of its commitment to the development of the security management system and to improving its effectiveness by:

- Appointing a member of top management who, irrespective of other responsibilities, is responsible for the design, maintenance, documentation, and improvement of the security management system

- Appointing members of management with the necessary authority to ensure that the objectives and targets are implemented

- Identifying and monitoring the expectations of the organization’s stakeholders and taking appropriate action to manage these expectations

- Ensuring the availability of adequate resources

- Communicating to the organization the importance of meeting its security management requirements to comply with its established policies

- Ensuring any security programs generated from other parts of the organization complement the security management system

- Communicating to the organization the importance of meeting its security management requirements to comply with its policy

- Establishing meaningful security metrics and measures of effectiveness

- Ensuring that security-related threats, criticalities, and vulnerabilities are evaluated and included in organizational risk assessments as appropriate. (See figure 3.)

- Ensuring the viability of the security management objectives, targets, and programs.

Figure 3: Security audits–Assessing risk

- Security policies

Top management must develop, as applicable to the mission of the organization, written security policies that are:

- Consistent with the other policies of the organization.

- Provide a framework for specific security objectives, targets, and programs to be produced.

- Consistent with the organization’s overall security threat and risk management strategy.

- Appropriate to the threats to the organization and the nature and scale of its operations

- Clear in their statement of overall/broad security management objectives.

- Compliant with current applicable legislation, regulatory, and statutory requirements and with other requirements to which the organization subscribes.

- Visibly endorsed by top management

- Documented, implemented, and maintained

- Communicated to all relevant employees and third parties including contractors and visitors with the intent that these persons are made aware of their individual security-related obligations

- Available to stakeholders where appropriate

- Provided for review in case of acquisition or merger or other change to the business scope, which may affect the relevance of the security management system

- Security risk assessment

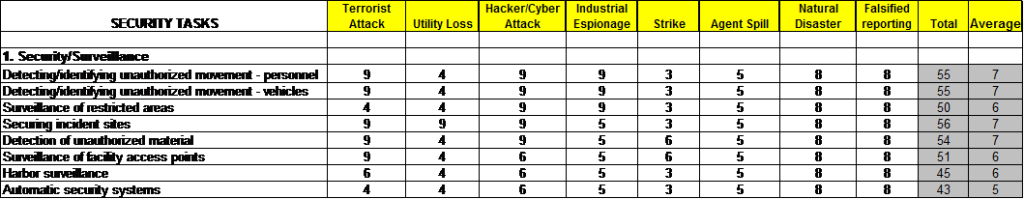

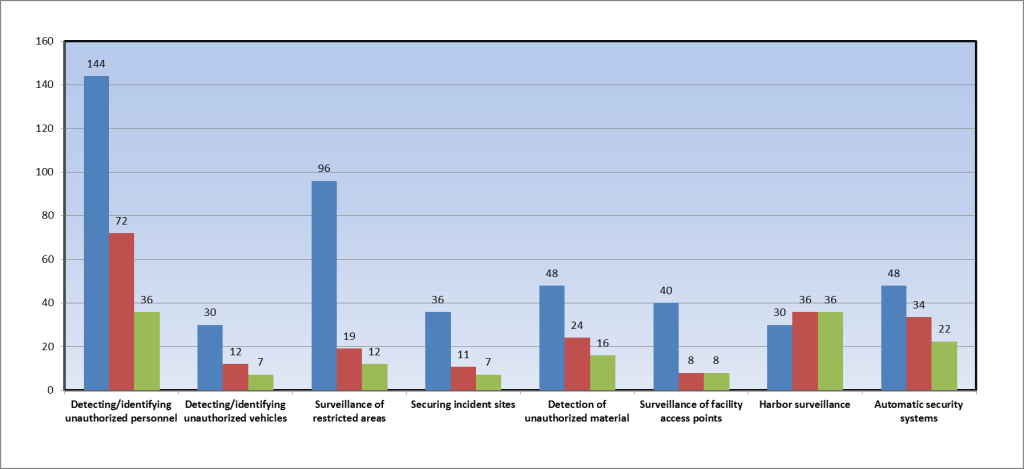

Security risk assessment, like any other focused risk assessment, requires the identification and assessment of the threats, criticalities, and vulnerabilities of the organization and its missions. The organization must establish and maintain a strategy for the ongoing identification, assessment, and mitigation of all its risks, including those related to organizational security. Mitigation means the identification and implementation of effective control measures or courses of action. It is in the execution of the control measures that risk assessment becomes risk management. We identify notional threats, apply them to different sub tasks, and assign numerical values, as shown in figure 4.

Figure 4: Security audits–Security risk assessment

The bar graph in figure 4 describes risk assessment of security sub-tasks. The bars reflect successively taking mitigations into account according to the following steps:

- Risk = Threat × Criticality × Vulnerability

- Adjusted risk = Threat × Criticality × Vulnerability × Environmental adjustment

- Predicted risk = Threat × Criticality × Revised vulnerability × Environmental adjustment

An effective security risk assessment strategy should include identifying (as appropriate):

- Physical failure threats and risks such as functional failure, incidental damage, malicious damage, or terrorist or criminal action

- Operational threats and risks, including the control of security, human factors, and other activities that affect the organization’s performance, condition, or safety

- Environmental or cultural aspects that may either enhance or impair security measures and equipment

- Factors outside of the organization’s control such as failures in externally supplied (e.g., outsourced) equipment and services

- Stakeholder threats and risks such as failure to meet regulatory requirements

- Security equipment, including replacement, maintenance, information and data management, and communications

- Any other threats to the continuity of operations

- Security training and qualification

A security-minded organization appoints (and entrusts) personnel to operate a security management system. Like any other responsible position, the people who design, operate, and manage the security equipment and processes must be suitably qualified in terms of education, training, certification, and/or experience. Further, these personnel must be fully aware and supportive of:

- The importance of compliance with security management policies and procedures and to the requirements of the security management system as well as their roles and responsibilities in achieving compliance, including emergency preparedness and response

- The potential consequences to the organization’s security posture by departing from specified operating procedures

- Operational control

Effective operational control of the security management system means that the organization has identified all operations necessary for achieving its stated security management policies, control of all activities, and mitigation of threats identified as significant risks. Control also means compliance with legal, statutory, and other regulatory security requirements, the security management objectives, delivery of its security management programs, and the required level of supply chain security.

ISO 28000 certification requires organizations to ensure that operational control is maintained by:

- Establishing, implementing, and maintaining documented procedures to control situations where their absence could lead to failure to maintain operations.

- Establishing and maintaining the requirements for goods or services that affect security and communicating them to suppliers and contractors.

Where existing designs, installations, and operations are changed, documentation of the changes should address attendant revisions to:

- Organizational structure, roles, or responsibilities

- Security management policy, objectives, targets, or programs

- Processes or procedures

Documenting the introduction of new security infrastructure, equipment, or technology should also include the introduction of new contractors or suppliers.

Almost every organization has some kind of supply chain. Whether upstream or downstream of its activities, the supply chain can have a profound influence on its operations, products, and services. Identifying, evaluating, and mitigating threats posed from supply chain activities are as essential as performing the same functions inside your own fence line. The organization requires controls to mitigate potential security issues and to other nodes in the supply chain as well.

- Communication and documentation

The organization must have procedures for ensuring that pertinent security management information is communicated to and from relevant employees, contractors, and stakeholders. This applies to outsourced operations as well as those taking place internally and is especially important when dealing with sensitive or classified information.

Additionally, the organization must establish security management system documentation system that includes but is not limited to:

- The security management system’s scope, policy, objectives, and targets

- A description of the main components of the system and their interaction and reference to related documents

- Documents including records determined by the organization to be necessary to ensure the effective planning, operation, and control of processes that relate to significant security threats and risks

- Emergency preparedness and response

Emergency response may be considered normal operations at faster-than-normal speeds or it may mean something entirely different. A security-minded organization must establish, implement, and maintain appropriate plans and procedures (e.g., backing up of records or files) for responses to security incidents and emergency situations. It must also prevent and/or mitigate the likely consequences associated with these risks. Emergency plans and procedures should include all information dealing with identified facilities or services that may be required during or after emergency situations to maintain continuity of operations.

Organizations should periodically review the effectiveness of their emergency preparedness, response, and recovery plans and procedures, especially after emergencies caused by security breaches and threats. Security-minded managers and auditors will test these procedures periodically, including scheduling drills and exercises in addition to security audits, and develop corrective actions as appropriate.

- Auditing and evaluation

Periodic internal or third-party security audits determine whether an organization is in compliance with relevant legislation and regulations, industry best practices, and conformance with its own policy and objectives. As with all audits, organizations need to maintain records of results, findings, and required preventive and corrective action.

Security-minded organizations need to audit their security management plans, procedures, and capabilities. Security audits can include periodic reviews, testing, post-incident reports and lessons learned, performance evaluations, and exercises. Significant findings and observations, once properly evaluated or gamed, should be reflected in revisions or modifications.

- Preventive and corrective action

Auditors discover nonconformities during audits. In doing so, we identify the need for either preventive or corrective action. Top management (hopefully) supports our audit findings and initiates preventive or corrective actions as appropriate. There is no difference with security audits. In fact, the need for corrective action may be even more acute after security audits.

- Continual improvement

Organizational effectiveness, the basis and underpinning of all of the standards produced by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), must be considered as an ongoing process and not an “end state.” It requires top management to develop a continuous improvement mindset that says that things can always be somehow improved. Continual improvement of organizational security requires top management to review the organization’s security management system at planned intervals to ensure its continuing suitability, adequacy, and effectiveness. Security audits and reviews should include assessing opportunities for improvement and the attendant need for changes to the security management system, including security policies and security objectives, plus threats and risks. Organizations already working with ISO 9001 and ISO 14001 can, with minimal effort, expand management reviews to cover security and well as quality and environmental management. A security management review, either as a stand-alone audit or as part of other management reviews (e.g., ISO 9001), should include:

- Evaluations of compliance with legal and regulatory requirements and other requirements to which the organization subscribes

- Communication from external interested parties, including complaints

- The day-to-day security performance of the organization

- Facility or physical plant security (including motion sensors, firewalls, and/or perimeter fencing)

- The extent to which stated objectives and targets have been met

- The security risk assessment strategy

- Status of corrective and preventive actions, and/or follow-up actions from previous management reviews

- Changing circumstances, including developments in legal and other requirements related to its security aspects

- Recommendations for improvement

Outputs from security management reviews should include any decisions and actions that change the security management system together with costs, schedules, and other justifications. They should be consistently committed to continual improvement.

Security audits–Summary

Organizations that cannot conduct their operations in self-imposed and self-monitored secure environments may cease to exist just as certainly as organizations that cannot maintain operational effectiveness, profitability, or product or service superiority. They must harden their operations through security audits to protect themselves from either incidental or deliberate attack. Auditors are essential to the hardening process, simply by doing what they do best: auditing.

About the author

Eugene A. Razzetti, CMC, retired from the U.S. Navy as a captain in 1992, a Vietnam veteran, and having had two at-sea and two major shore commands. Since then, he has been an independent management consultant, project manager, and ISO auditor. He became an adjunct military analyst with the Center for Naval Analyses after September 11, 2001. He has authored two management books and co-authored MVO 8000, a corporate responsibility management standard, and is an adjunct lecturer on strategic management and ethics at Argosy University. He is a certified management consultant with the Institute of Management Consultants and has served on boards and committees dealing with ethics and professionalism in the practice of management consulting. He is a senior member of the American Society for Quality and recently assisted the government of Guatemala with the ISO 28000 certification of its two principal commercial port facilities. He can be reached at www.corprespmgmt.com or generazz@aol.com.