By Chad Kymal

Last time in this column, we discussed the global standards around carbon neutrality. For this month’s column, I’d like to touch on a different, but somewhat related topic: The advent of electric and autonomous vehicles, and what that revolution will mean to those in the conformity-assessment and management system auditing communities.

According to America’s Zero Carbon Action Plan, the transportation sector currently accounts for a whopping 28 percent of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. Phasing out the nation’s millions of internal-combustion engine cars, trucks, and buses and replacing them with new electrified vehicles is seen as a major effort to reduce carbon emissions.

Specific governments and corporations have set specific and aggressive goals in this realm. For example, the state of California is planning for 100-percent electrified light-duty vehicle sales by 2035, and 75 percent of truck sales by that same date.

The year 2035 seems to be a magic target date for other entities as well. China has committed to 100-percent electrification of the cars on its roads by that date. General Motors likewise pledges to stop selling internal-combustion vehicles by then.

A dramatic shift is taking place in the industry’s adoption of electric vehicles. This naturally means a great amount of electronics and batteries in these vehicles, which means that safety is an even bigger concern than ever before. Additionally, because these new cars are so connected, cybersecurity becomes a big concern as well. Software and electronics are increasing front-and-center for these cars; for this reason, big players and new entrants from Silicon Valley have become very interested in the industry. Safety and cybersecurity is paramount, software is running into millions of lines of code, and there’s a tremendous amount of new hardware systems being implemented.

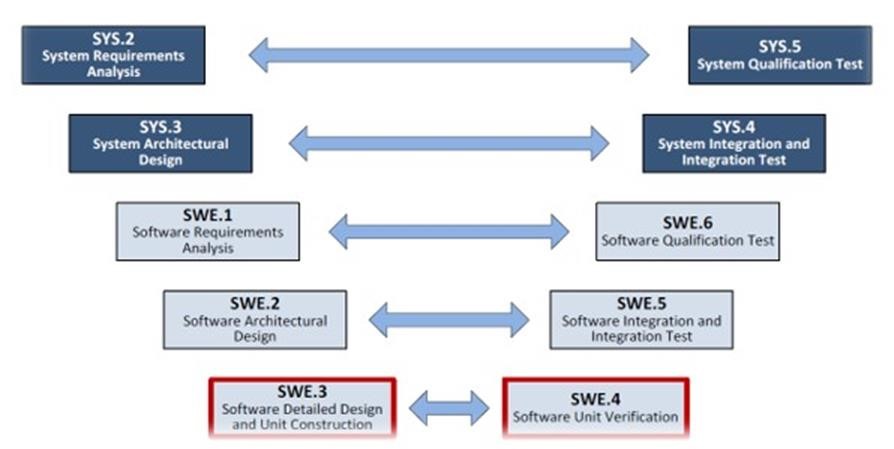

Another important element to note is that product development is witnessing major upheavals, with fundamental changes, particularly affecting design and engineering functions. Automotive OEMs have never designed like this before, so they have adapted their systems engineering within the V-Model framework, as seen in figure 1. This framework allows manufacturers to connect themselves with their suppliers all the way down the supply chain. I’ve therefore coined the term, “design supply chain,” as opposed to the manufacturing supply chain, because of the sheer amount of design information going to and from these suppliers.

Figure 1: V-Model

In response to the growth of electric and electronics-connected vehicles and their software systems, manufacturers and suppliers have come to rely on new standards such as ISO 26262 for functional safety, automotive SPICE covering software, and ISO 21434 on cybersecurity. Because of these new requirements, product development must completely change. All requirements from the system level flow all the way down to semiconductor chips. This is a huge change, and it’s particularly daunting for the new entrants coming into the automotive industry. Many don’t fully understand that they will have to implement IATF 16949, ISO 21434, ASPICE, and ISO 26262 at a minimum.

This is all extremely relevant to management system auditors who work within the automotive industry. They cannot just walk into an auditee’s site and start auditing ISO 26262; what’s needed is a rather specific background and understanding of the intent of these new standards. It can be picked up with practice, however. Right now, what we expect is that an auditor can work with a typical automotive standard like IATF 16949, but they may not yet see where ISO 26262, ASPICE, and ISO 21434 fit into the picture. There’s lots of overlap between these standards, and the worst thing that a company—or auditor—can do is attempt to implement or assess them in a standalone fashion, because the product and design functions are now closely interconnected.

Of course, electric cars are only one part of a rapidly changing industry. Autonomous vehicles will demand even more complex design, production, and testing systems, all of which will need to be assessed by qualified auditors with deep understanding. It’s breathtaking to consider the potential revenues that autonomous vehicles could generate for legacy OEMs and new entrants. I like the chart seen in figure 2, because it demonstrates the five levels of automation for cars. We are right now in level 2 (partial automation), and some cars coming out are reaching level 3 (conditional automation). But level 4 (high automation) is what cars and trucks need to achieve as soon as possible. Level 4 automation means that cars can autonomously drive from one city to another along the highway. Everyone is betting on level 4 automation, and the company that gets there first will dominate the market. Incidentally, beyond that, at level 5, you’ll be able to sit in your home and order a car, which will show up and take you wherever you want to go. When level 5 autonomy is accomplished, the amount of people driving will drop dramatically.

Figure 2: SAE Levels of Automation

There’s another new standard, ISO 21448, which addresses safety of the intended functional (SOTIF). This standard helps OEMs and suppliers think through hundreds of thousands of scenarios of what could happen with autonomous vehicles in the real world. Everyone is looking to test what are known as “edge conditions.” What are edge conditions? Let’s say I’m traveling in an autonomous vehicle, and I want to pass the vehicle in front of me. I move to the left automatically, and I pass. But what if the car in front speeds up? What if a motorcycle speeds up right when we’re moving over to the left-hand lane? What if a child crosses the road unexpectedly? We need to think through these scenarios and make sure that the car can handle itself. That is where this SOTIF standard comes into play.

From the auditor viewpoint, the management system standards will have to change to account for the V-model. They will also have to synergize with ASPICE, some of which already started back in 2016. Manufacturing itself will have to change, because the auditor will need to follow the trail from the OEM’s safety requirements and determine traceability all the way down to a widget that goes into a sub-subsystem that goes into a subsystem that goes into a system that goes into a car. Walking that plant, an auditor will have to trace it all the way. It is one of the requirements of the standard. Suddenly, configuration becomes very important.

Auditors are going to have to learn and change. If they have the mindset that they cannot audit hardware and software, then their days are numbered. Although many of us were trained as mechanical engineers and/or working within typical combustion-engine production systems and supply chains, change is possible. Bravery and confidence are necessary for success during this transformative period. After all, it’s only auditing and assessing, and with some practice, I’m sure that the auditors reading these words will be able to do it.

If you can’t do it, well, then your future is uncertain—just as uncertain as the manufacturers and suppliers themselves who will not or cannot adjust to these new realities. The opportunities are there. Are you ready to seize them? Visit Omnex’s training site if you are looking to learn more about any of the standards mentioned, and please leave a comment below with your thoughts on these important topics.

About the author

Chad Kymal is the CTO of Omnex Inc., an organization that audits, trains, and implements various standards. He is also founder of Omnex Systems, which develops EwQIMS software.