By IJ Arora, Ph.D.

The choice between writing a procedure or a work instruction is an essential decision when designing a management system. Clause 4.4.1 of ISO 9001:2015 (as well as all the ISO management system standards using the harmonized structure) requires the establishment and implementation of a management system. This management system will have procedures and work instructions and further down the hierarchy, checklists and forms.

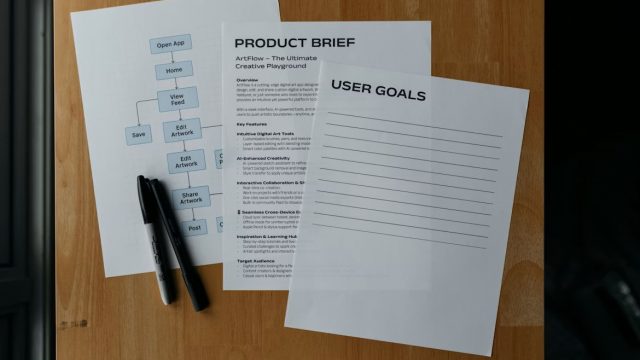

Processes can be actualized in many forms. Today, mapped processes make it easy to visualize the functioning of the process. This is an important distinction in quality management systems based on ISO 9001—or for that matter any sector-specific standard like those dedicated to management within maritime, aerospace, etc. Many organizations struggle with when to write a procedure, when to write a work instruction, and how and when a flowchart should be used.

I think the core difference between a procedure and a work instruction is that a procedure answers the question, “What happens and who does it?” A procedure defines the process, its purpose, its sequence (clause 4.4.1b), and who is responsible for the work, perhaps as process owners (clause 4.4.1e). It answers what is to be done, when it must be done, who is responsible, and why it matters. The flowchart then helps visualize the inputs and outputs that flow between the steps.

What is a procedure and how it is used?

A procedure does not tell someone how to do a task; it simply describes the steps or stages necessary to accomplish it. I think of the procedure as the blueprint of the workflow. Therefore, I would recommend using the procedure when multiple people or departments are involved, when there is decision-making or sequencing, when the process crosses functional boundaries, and when documenting the process supports consistency, audits, or training. The procedure is also best when regulatory bodies expect clearly defined processes.

What is a work instruction and how is it used?

On the other hand, a work instruction shows stakeholders how exactly a task is to be accomplished. A work instruction “goes into the weeds” to the extent required by the workforce (depending on their confidence, competence, knowledge, and so on). It describes specific methods, often at a deep level of detail. It answers questions such as:

- “How do I perform this task?”

- “What tools, equipment, settings, forms, and/or software steps are required?”

- “What are the acceptance criteria?”

- “What do I check and how do I measure performance?”

Remember, work instructions are intended to be simple, direct documents for use by the workforce. Use them when:

- A task requires technical, step-by-step details

- Training new personnel

- Incorrect execution can create quality or safety risks

- Standardization is essential

- Variation in execution must be eliminated

What is a flowchart and how is it used?

Flowcharts can technically be used to support both procedures and work instructions, but I generally recommend their use in conjunction with procedures. This helps make the procedure visual by mapping the 50,000-foot view of a process. A flowchart is ideal when the process has multiple decision points, parallel paths, several departments interacting, and inputs/outputs that must be made clear. The flowchart helps avoid the confusion that can come when procedures are described in long paragraphs. Flowcharts make complex processes easy to understand immediately. I therefore believe in flowcharting a procedure when the process needs high-level clarity, the sequence matters, when an organization wants to show interactions between departments, when it supports risk-based thinking, and when you want to simplify training for new personnel.

Flowcharts work best for document control, nonconformances, and corrective action processes, purchasing and supplier management, production scheduling, quality inspection, and testing flows and change management processes (as seen in clauses 5.3e, 6.3., 8.2.4, 8.3.6, and 8.5.6). Flowcharts do not replace work instructions; they complement them.

Final thoughts

To sum up how these tools work together, the practical document hierarchy an organization could consider starting with policy (and why that policy exists), move into documenting the procedure (preferably supported by a flowchart) to convey what happens and in what order, and then crafting work instructions to clarify how to carry out specific tasks. Finally, document everything through records and forms to provide evidence that the work was performed.

All this should connect as a system where a flowchart procedure should describe the process, a work instruction explains each critical task, and the documented information provides traceability. Performance monitoring (clause 9) can be documented via procedures, work instructions, and flowcharts.

About the author

Inderjit (IJ) Arora, Ph.D., is the Chairman of QMII. He serves as a team leader for consulting, advising, auditing, and training regarding management systems. He has conducted many courses for the United States Coast Guard and is a popular speaker at several universities and forums on management systems. Arora is a Master Mariner who holds a Ph.D., a master’s degree, an MBA, and has a 34-year record of achievement in the military, mercantile marine, and civilian industry.

For managers in high-stress professions like the military where bad decisions (made with the best intentions, in seconds) can lead to a very considerable loss of lives; after sufficent years in uniform, one intuitively develops organisational skills that are ingrained in the processes described here. However, the manner in which it is all spelt out in this article, provides a specific framework to measure your battle-honed skills against well calibrated, carefully established yardsticks. For those organisations where wrong actions and decisions will lead, at worst, only to money losses and unfortunately, laid off workers with families to feed, this is a very important tool to get the best financial results.