by Bill Combs

Recessions such as the United States has been enduring for the past two years provoke predictable, fairly standard responses from individuals, businesses, and government, which all face real threats from budgetary constraints and reduced cash flows. The typical response tends toward the conservative: Cut back, spend less, save more. Those approaches are understandable and justifiable; most agree that the current recession is the greatest threat to the U.S. economy since the Great Depression. Given the dimensions of the recession, who isn’t interested in managing costs?

What’s been unexpected is that along with increasingly limited resources is a concomitant increase in demand for high-quality goods and services. That’s one factor that causes this recession to defy expectations—despite a desire to return to normal times, recovery is tepid and a lack of consumer confidence in the quality of U.S. goods combined with an unwillingness to invest in long-term solutions to address that issue contributes to a persistent stagnation in productive output.

Clearly, there are effects on quality practitioners and auditors—but what are they? What can we expect over the long term? In this article, I will address these questions by looking at the trends that were in place before the recession and suggest how the auditor’s role needs to change as we endure a long and difficult recovery.

One economic factor that has not been affected by the recession is the adoption of technology. One has to question whether auditing has kept pace with the rate with which the market demands technology. Ray Kurzweil demonstrated in 1991 that early adoption of technology has expanded in a log10 progression over the last century. For example, in 1910, just ten years after electricity was widely available in various local markets, 2 percent of homes in those markets had electricity. In 1930, ten years after the first commercial radio broadcast, 1.8 million radios were in use, an equivalent percentage relative to the population as a whole. By comparison, ten years after the Internet was available, it had 230 million users.

Wide early adoption of telephone, television, and mobile phones just ten years after their introductions suggests an upward trend in a logarithmic progression. One factor contributing to the growth of early technology adoption is that the population of the United States increased tenfold over the 20th century, reaching 308 million by 2010. But population growth notwithstanding, the early adoption of technology has grown at a geometric ratio over the past century, a ratio that Kurzweil likened to a log10 scale. Another driver behind such a growth in early adoption is a net drop in cost.

There is little question that technology and technological products are of exceptionally high quality at very favorable costs to the consumer. Clearly, technical products marketed on a mass scale are generally solid and reliable, and one can reasonably expect that they will continue to function well. However, it’s no longer a reliable device per se that consumers want to buy; it’s their function that consumers want. This element illustrates a little-noticed but significant trend in U.S. productivity: From the middle of the 20th century and into the first decade of the 21st, the U.S. economy stopped its focus on being a producer of products and became a provider of services instead.

Regarding our example of the role of technical devices early in the 21st century, one has only to recall his or her most recent call to a technical support center. How many calls begin with the explanation that “This call may be monitored for quality purposes,” or end with a cheery “How else may I provide excellent customer service?” Given this far-reaching shift away from products and toward services, one has to question the extent of quality processes’ ability to adjust accordingly and provide consistent, quantitative ways of measuring and improving services.

The focus on services isn’t misplaced. In fact, the shift from a manufacturing economy to a service economy began in earnest after World War II. Service employees now outnumber manufacturing employees by five to one. This is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1: Economy trends, services, and quality auditing:

|

||

| Billions ($) | Percent (%) | |

| Total GDP | 14,143.3 | 100 |

| — | — | — |

| Personal Consumption | 9,996.6 | 70.7 |

| Goods | 3,191.0 | |

| Services | 6,805.3 | |

| — | ||

| Gross private domestic investment (PDI) | 1,558.6 | |

| Net import/exports of goods and services | (338.7) | |

| Gross PDI plus Exports less Imports | 1,219.9 | 8.6 |

| Exports | 1,492.2 | |

| Goods | 977.7 | |

| Services | 514.4 | |

| Imports | 1,830.8 | |

| Goods | 1,460.6 | |

| Services | 370.2 | |

| — | ||

| Federal consumption and investment | 1,137.0 | |

| National defense | 775.0 | |

| Nondefense | 362.0 | |

| State and local consumption and investment | 1,789.8 | |

| Gross government consumption and investment | 2,926.8 | 20.7 |

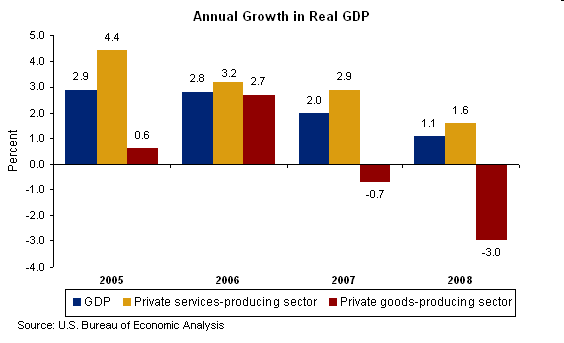

Figure 2 illustrates that consumers value services twice as much as products. Furthermore, recent trends indicate that in the middle of an overall decline in economic growth, the production of goods can no longer be a reliable contributor to economic growth.

Figure 2: Economy trends, services, and quality auditing: Annual growth in real GDP

The general indication is that quality programs, including the role of auditors, can no longer emphasize an expensive and unsustainable focus on production lest that emphasis be intertwined with a diminishing factor in the economy. Our problem is compounded because of the tendency of goods and services providers to reduce overhead costs in recessionary times. The launch of new products, for example, carries with it inherent risks and expense. RTM suggested in 1999 that for every 3,000 new ideas, there are roughly just two products that are launched; only one is successful.

There’s no question, of course, that quality is important in new product launches; after all, who wants a product to fail? Further, a focus on quality and the ability to quantify issues and then address them systematically and repeatedly enhances the new product’s chance in its market. But in the face of these numbers, quality finds itself in the position of having to come to terms with an unpleasant perception: Why continue to invest in a process in which most of its efforts will be wasted? Given the relatively poor ratio of product ideas to successful new product launches, an intriguing question can be raised: where are the raw, unwritten ideas that would lead not to the launch of a viable product, but instead to the launch of a successful service?

Since the beginning of the total quality management (TQM) movement, service providers have bemoaned the relative lack of models by which the efficacy of a new service could be assessed. To counter the expenses associated with new product development and to reflect the growing trend to provide substantially more services, this recession suggests that more auditing professionals could more profitably spend more time developing models of assessing the quality of services instead of demanding adherence to products-focused standards that have little demonstrable return.

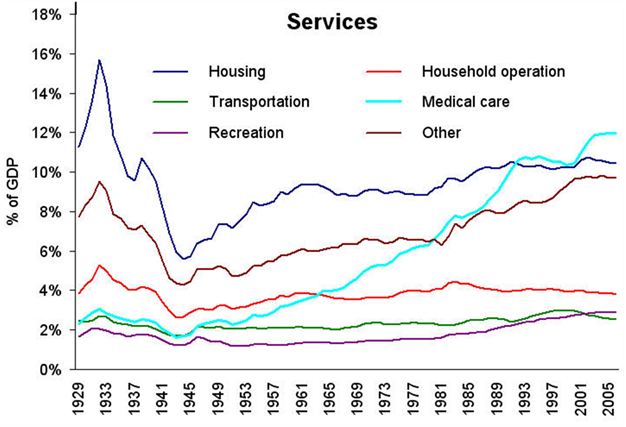

Where, then, should quality focus its efforts? What do the trends suggest are the bright spots, the areas in which quality services will be most demanded? Trend data suggest that substantial opportunities exist, though in areas typically not associated with quality processes. Over the 20th century, for example, the evolution of the U.S. economy into a services economy illustrate where spending has occurred, as illustrated in figure 3.

Figure 3: Economy trends, services, and quality auditing: Services in the U.S. economy

The volume of spending is so substantial it can easily be subdivided into broad categories. Though the recession is a factor that negatively affects the gross domestic product (GDP), spending will not be as subject to the fluctuations associated with the Great Depression (a peak, resulting from New Deal spending), and World War II (a trough, associated with wartime economies). Medical care will continue to lead spending in service areas as Baby Boomers continue to retire and continue to age well into the current century. Housing will also continue to be a factor as homeowners fix up, repair, or position properties for resale. The “other” category, which includes a range of personal services, education, social care, and consumer spending for other than durable goods is positioned for slight increases. Household operations, transportation, and recreation appear to be stable, though substantial factors in spending on services.

Government will also continue to be a driver of services. Outside of some defense procurement programs for big-ticket items for shipborne, air, ground, and missile defense, the Pentagon’s need for services will show a relative increase. Although defense spending will remain stable, the numbers of federal employees supporting the Department of Defense will decrease. This means that the same level of services-related work will increasingly pass to outsourced service providers, thus extending the trend toward a service economy in the federal market. Spending for services in state and local governments will continue to outstrip federal spending by a third, as is currently the case. Quality processes have a relatively low profile in state and local services. Does the lack of a quality focus contribute to the relatively high level of spending for public services? This question deserves a response, and state and local spending represents a substantial opportunity for quality in the decades ahead.

There’s one last broad area that deserves attention. Currently, the United States is experiencing a trade deficit in products: We import foreign products valued at a half billion dollars more than we export. The only favorable trade balance pertains to services—the most recent GDP figures illustrate that the United States is exporting services at a rate of $50 million more than we currently import. Not only do those numbers indicate the extent to which the transition to a services economy is complete, but it suggests something about foreign markets: they will continue to grow, while the North American market will grow at a smaller net rate.

A few months ago, The Economist reported that the population in North America is roughly 352 million and is expected to reach nearly 450 million by 2050. By contrast, Africa’s current population of just over one billion is expected to grow by nearly 50 percent, reaching nearly two billion by 2050. China’s population of just over 1.3 billion will reach 1.4 billion by 2050, even with the same percentage growth expected in North America. The potential market for services within North America will thus continue to diminish in the face of emerging markets that will become dominant consumers over just the next 40 years.

Have U.S. service providers come to terms with a shifting market? And to what extent will quality professionals be willing to abandon processes that once served a manufacturing economy and adopt processes appropriate to services providers in a global economy?

There’s no question that the U.S. economy has been based on the delivery of goods and services on a large scale, responsive to market demands, and of a certain quality that led to an understanding that American know-how was a mighty force, capable of delivering world-class goods and services. But the world continues to change, will quality providers do the same?

About the author

Bill Combs has more than 15 years of experience in quality programs in corporate and information technology training. He is currently a senior training specialist at a major consulting company.

Tags: economy, quality auditing, total quality management.